Composition

Composition is a fundamental concept in C++ that allows you to build complex classes by combining smaller, more specialized classes. In this section, we’ll explore how composition works and why it’s a powerful way to design and organize your code.

We’ll also cover several advanced topics that weren’t discussed in the previous lesson, such as the principle of least privilege, constant functions, constant objects, initializer lists, friends of a class, operator overloading, and how to chain function calls.

What Is Composition?

Section titled “What Is Composition?”In C++, composition refers to a “has-a” relationship between classes.

One class, say Class A, includes one or more objects of another class,

Class B, as its data members. This allows Class A to leverage Class B’s

functionality without needing to know or depend on how Class B does its job.

Key Points

Section titled “Key Points”-

“Has-A” Relationship

-

If Class

A“has a” ClassB, it meansAhasBas a data member. -

Example: A

Carclass might have anEngineobject, aTransmissionobject, and so on.

-

-

Independence of Implementation

-

Class

Adoesn’t care how ClassBdoes its job; it only cares thatBprovides certain capabilities. -

This keeps the two classes more loosely coupled and easier to maintain.

-

-

Include the Header

- In Class A’s header, include Class B’s header so you can declare

Bobjects inA.

- In Class A’s header, include Class B’s header so you can declare

#include "B.h" // Path to Class B’s header

class A { private: B objB; // A has-a B // ...};-

Separate Object Code

-

Ensure Class B’s implementation (its

.ccfile) is compiled and linked in the final project alongside ClassA. -

Class

Awill call B’s functions throughobjB, but it doesn’t need to worry about the details in B’s.cc.

-

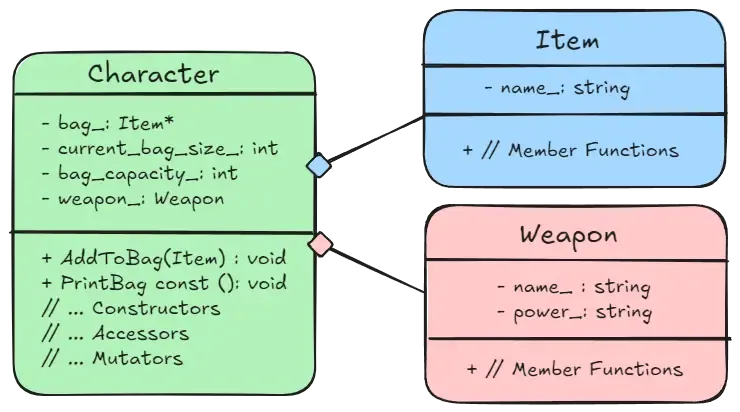

UML Diagram

Section titled “UML Diagram”The following figure shows a UML Diagram of a “has-a” relationship between classes. A diagram similar to this is likely to show up on an exam. The key difference between other diagrams is that a diamond like shape is attached to the line.

More About Classes

Section titled “More About Classes”This section delves deeper into several class-related features that may have been mentioned before, but not fully explored. These details will help you refine how you design and interact with classes, improving both code clarity and reliability.

Principle Of Least Privilege

Section titled “Principle Of Least Privilege”Now that your classes are going to interact with each other, it’s important to decide what data and behaviors should be visible or modifiable by outside code. The Principle of Least Privilege states that functions, classes, and other parts of your program should be given only the minimum access rights needed to do their jobs—no more.

To adhere to this principle in C++, you’ll often:

-

Mark data members and functions as

privateorprotectedunless they need to be accessed externally. -

Use the

constkeyword liberally—to declare variables, parameters, member functions, and even entire objects as constant—whenever their values or behaviors should not change.

Constant Functions

Section titled “Constant Functions”A constant member function is declared with the keyword const at

the end of its signature (in both the prototype and the implementation).

Marking a member function as const promises the compiler—and other

developers—that this function will not modify the object’s state.

It also means the function cannot call any non-const member functions, ensuring the object’s data remains unchanged.

We label it when defining our class in the header file:

class Character { public: int GetHp() const;

private: int hp_;};We also label the function const when we write the implementation in

a source file:

int Character::GetHp() const { return hp_; }When Is This Useful?

Section titled “When Is This Useful?”-

Read-Only Access: If a function’s purpose is simply to inspect or retrieve data without altering it—like a “getter” method—declaring it as

constclearly expresses its intent and enforces it at compile time. -

Error Prevention: If you accidentally try to modify the object’s data inside a

constfunction, the compiler will generate an error, catching potential bugs early. -

Better Design: Declaring functions as

constwhenever possible helps you follow the Principle of Least Privilege, making your code more predictable and easier to maintain.

Constant Objects

Section titled “Constant Objects”Just like you can declare a const int or const double, you can also

declare an entire object as const. Although this scenario probably won’t appear

in an assignment, it’s a concept that may come up in an exam.

-

Immutable State: A constant object cannot be modified after it is created. Any attempt to change its data members will result in a compiler error.

-

Calling Only Const Member Functions: Because a constant object must remain unchanged, it can only call constant member functions—those declared with the

constkeyword at the end of their signatures.

int main() { const Character hero; int hp = hero.GetHp(); // Allowed since its a constant function hero.SetHp(200); // Error cannot call non-constant function

return 0;}Initializer List

Section titled “Initializer List”In C++, an initializer list allows you to initialize your class members

before the constructor’s body executes. It appears after the constructor’s

parameter list, starting with a colon (:) and followed by a comma-separated

list of initializations. For example:

Character::Character(string name, int health) : name_(name), health_(health) { // Constructor body};Why Use An Initializer List?

Section titled “Why Use An Initializer List?”-

Order of Initialization: Members are initialized in the order they’re declared in the class, not the order they appear in the list. Using an initializer list clarifies that order and can help avoid issues when you depend on one member being initialized before another.

-

Immutable Members: If you have

constdata members or references, you must use an initializer list to set their values. -

Efficiency: Initializing members directly is often more efficient than assigning to them in the constructor body because it avoids unnecessary default constructions or assignments.

Friends

Section titled “Friends”In C++, you can designate non-member functions or other classes

as “friends” to grant them direct access to your class’s private

data members. This mechanism is especially useful for operator

overloading in situations where the operator can’t be defined as

a member function, such as the stream insertion (<<) or extraction (>>)

operators.

Here’s an example that uses a friend function to overload the << operator

for printing:

#include <iostream>#include <string>

using std::cout;using std::endl;using std::ostream;using std::string;

class Character { public: friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& whereto, const Character& c) { whereto << "Name: " << c.name_ << endl; whereto << "Hp: " << c.hp_; return whereto; }

private: string name_; int hp_;};Here’s a breakdown of the friend function:

- Operator Function

-

The

&operator<<function is an overloaded operator that customizes how the<<operator behaves for a user-defined class. By default, the<<operator is used to output data (e.g., tostd::cout), but it doesn’t know how to handle objects of custom types likeCharacter. -

operator<<: The<<operator is overloaded as a non-member function.

- Friend Declaration

-

The

frienddeclaration appears inside the Character class but outside of any member function. -

The

friendkeyword tells the compiler that theoperator<<function is allowed to access the private members (name_andhp_) ofCharacter.

- Ostream

-

The

ostreamclass, part of the Standard Library, is used for output streaming in C++. It represents output destinations like the console (std::cout) or files. -

It is used as the first parameter of the

operator<<function to specify where the data should be sent. -

By returning the

ostreamreference, the function allows chained calls:

cout << hero << " is ready for battle!" << endl;- You must include

<iostream>and usestd::ostreamorusing std::ostream;to use it.

Unlike other functions, if you want to write the implementation, you do not tie the

function to the class because it is not a member function. You also omit the friend keyword:

ostream& operator<<(ostream& whereto, const Character& c) { // Implementation... return whereto;}Key Points

Section titled “Key Points”- Declaring A Friend

-

By prefixing

friendto the function prototype, you explicitly grant the function access to the class’s private members. -

This is critical when overloading certain operators (like

<<and>>) that cannot be defined as member functions in a straightforward way.

- Other Uses Of Friend

-

The

friendkeyword can also be used to allow another class direct access to this class’sprivatedata, even if it’s not a child class. -

In other words, you can declare

friend class SomeOtherClass;in the same way you declare friend functions.

- Properties Of Friends

-

Given, Not Taken: The class itself must explicitly name the function or class as a

friend; you cannot request friendship from outside. -

Not Symmetric: If Class

Adeclares afriendfunction or class, thatfrienddoes not automatically treatAas afriend. -

Not Transitive: If Class

Ais friends with ClassB, and ClassBis friends with ClassC, ClassAis not automatically friends with ClassC.

Overloaded Operators

Section titled “Overloaded Operators”In C++, you can overload many built-in operators to work with

your custom classes. Generally, you declare the overloaded

operator as a member function if (and only if) the left

operand of the operator is an object of your class.

For operators where the left operand is not an object of your class

(for example, the stream insertion operator <<, where the left operand is std::ostream),

you must define it as a friend function (like the previous section).

The Rule Of Three

Section titled “The Rule Of Three”If you worked through the Basic Example in the previous lesson, you saw that having a pointer as a data member required you to customize a copy constructor and to customize a destructor. The final requirement when you have a pointer as a data member is that you overload the assignment operator:

We first define it in a header file:

class Character { public: Character& operator=(const Character&);

private: string name_; string* bag_; int bag_size;};We return a reference so we can mimic built-in types in chaining assignments,

and to avoid unnecessary copying of objects:

Character a, b, c;a = b = c;Then we write the implementation in a source file. If you remember the example code for a customized copy constructor in the previous lesson, then this code will look very similar. The key difference is that the assignment operator is being called on an existing object, so we have to delete the current pointer members to release memory.

Character& Character::operator=(const Character& c) { name_ = c.name_; bag_size_ = c.bag_size_;

// Here is the difference between a copy constructor if (bag_ != nullptr) { delete[] bag_; }

bag_ = new string[bag_size_];

for (int i = 0; i < bag_size_; ++i) { bag_[i] = c.bag_[i]; }

return *this;}Key Rule To Remember

If you have a pointer that is a data member, you should always create the following:

-

Copy Constructor: so each new object allocates its own copy of the data

-

Destructor: to release the dynamically allocated memory

-

Overload Assignment Operator: so that assigning one object to another correctly copies the data

Chaining Functions

Section titled “Chaining Functions”Function chaining allows you to call multiple member functions in succession,

using the dot operator to produce clean, fluent code. To enable this, make a

function return a reference to the current object (typically *this), rather

than returning void.

The implementation is included with the class definition only for example purposes:

class Character { public: Character& SetName(string name) { if (name != "") { name_ = name; } else { name_ = "none"; }

return *this; }

void PrintName() const { cout << name_ << endl; }};Now we would have the option to set a character’s name and immediately print it after:

Character c;c.SetName("Zidane").PrintName();